M Y T H O L I G I E S o f t h e S P I R I T

by J o h n W o o d

from Contact Sheet / Light Work Annual 2007

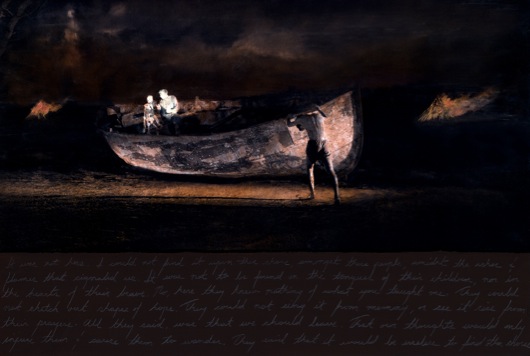

Don Gregorio Antón’s photographs radiate compassion like the work of no other living artist I know. They are filled with an intense humanity we usually find only in a few documentary photographers and photo-journalists—the Gene Smiths, Salgados, and Nachtweys. Antón is, however, a different kind of photographer, though one could call his work a document of the spirit, the journal of a sacred quest. But his photographs are not even photographs in the usual sense of the word—those captured moments of a past reality, be they taken by someone’s uncle at a family picnic or by Paul Strand in a French village. His images, though equally real, are constructions of psychological realities, portrayals of mythic fears, sacrifices, and hopes.

Such photographs come as knife-thrust-shocks because they carry emotions we’re unused to seeing in imaginative and seemingly imaginary work. We expect great documentary photographs, those instants seized from the most desperate flow of reality, to be tortured acts of compassion. We know they wounded their photographers as they took them. We don’t expect that in other kinds of photography, yet Antón’s work affects us in the same way as he interweaves and counterpoints his themes of hope and suffering.

These themes have been yoked in art before: some of the world’s greatest altarpieces were created for hospices so that the dying might be comforted in their suffering. Grünewald’s Issenheim altarpiece depicts a crucified Christ whose wrecked body could be mistaken for one of the plague victims who would have gazed upon it, and van der Weyden’s Last Judgment at the Hospices de Beaune is far more beatific than terrifying. Antón’s art, like theirs, is about hope because he knows our reality is suffering. Siddhartha knew the same thing and recommended we quench our desire. But Antón knows desire courses through us as elementally as our blood, so in his art he suffers with us.

When I first saw Antón’s work—and that was years before he began his series of Retablos—I could see he was a rare, saintly artist who, like Fra Angelico, dispensed solace with comfort. But his vision is radically different from Fra Angelico’s for it derives not from the Tuscan sun but from the more sober Mexican moon. In that reflected light of many Antón photographs, death, suffering, and dark gods with no taste for drink light as wine still hover near. The ghost of Bacchus yet haunts Italy’s Catholicism, but it’s Huitzilopochtli that broods over Mexico’s. Antón knows this, and his Retablos blend the physical form of a somber, Mexican religious and folk expression with his own dark, mystical imagery.

Traditionally painted on a small sheet of tin and hung in one’s home, retablos are devotional paintings, personal altarpieces, usually of the Virgin, Christ, or a saint. They were pleas, cries to saints for help when we are hopeless and feel there is no help. They were and are little plaques of hope, encouragement, and strength. Antón took the retablo, an object of cultural and emotional significance to him, and, in a stroke of genius, reinvented it within his own art. He changed its form from tin to enameled copper and its content from the saints of the Church to those of his own pantheon. He makes us think of Blake, another mystic, who did a similar thing in his Prophetic Books, which like Antón’s Retablos are visual and verbal mythologies of the spirit.

In the presence of such art we are in the presence of the sacred.

John Wood has written and edited over thirty books, including seven award-winning ones, on photographic history and on such contemporary photographers as Sally Mann, Joel-Peter Witkin, Flor Garduño, Luis González Palma, Brigitte Carnochan, and Eikoh Hosoe. He co-curated the

National Museum of American Art’s photographic exhibition Secrets of the Dark Chamber, is editor of 21st Editions, and for thirty years taught at McNeese University where he was Director of Graduate Studies in English and held professorships in both English literature and photographic history.

__________________________