D O N G R E G O R I O A N T Ó N

O L L I N M E C A T L : T HE M E A S U R E o f M O V E M E N T S

by H a n n a h F r i e s e r

from Contact Sheet no. 145

Don Gregorio Antón’s work has been described as “radiating compassion”, “at once tender and forceful, hushed and thunderous”, and as an “opportunity to see the richness and undeniable power of hope”. Sometimes the work is reminiscent of distant ancestral memories, while at other times his images remind of dreams experienced with a clarity that can only be felt in the moment of waking.

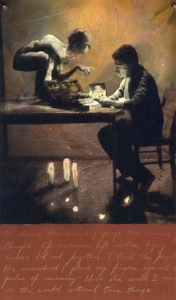

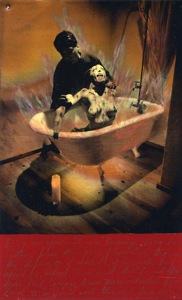

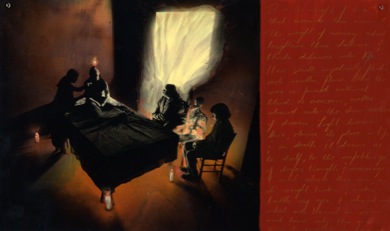

To enter the mystical world of Antón’s retablos it is necessary to set aside the assumptions that guide us through our daily lives. We have to surrender to his evocative images that are unfamiliar to our mind, yet resonate within our souls. Antón creates a world full of mystery, where life and death are not binary opposites, and where emotions are assets as powerful and tangible as a vault of money might be in our normal existence. In Antón’s world pain and fear coexist with bliss and euphoria, neither able to survive without at least a little of the other.

Antón’s work is likely to provoke a different response in every viewer. the retablos can be appreciated for their enigmatic beauty, their haunting narratives, or their intense spirituality. Where we find ourselves in our lives may be where we find ourselves in Antón’s imagery, so it is up to each person to find his or her own way to his world. Antón has tightly woven his cultural identity into this body of work. through the imagery and text of each retablo he describes and reforges his connectedness to his roots in Mexico. The writing on some retablos is easy to read, while the words on others fade into the background like melodies half remembered. Not unlike diary entries, the writing is deeply personal and vulnerable to exposure. As he writes on one of his retablos, “Every word, every image is inked in my blood. Each page burns, consumes, and carries the weight of memory, the weight of life.”

The work describes a mysterious and otherworldly existence that most of us experience only through dreams or nightmares. Linear time does not exist, and raw emotions are laid out in the open. Antón’s world is not defined as pain and suffering, though both appear frequently in the images. Rather suffering, pain, and fear are invited and accepted as players within the timeless cycle of life, along with bliss and salvation.

To the Western eye Antón’s world may seem like a primal realm. Most of us do not entertain such a non-threatening relationship with death and pain that we would invite corporal manifestations of these experiences to the dinner table, yet such is the case in Antón’s images. On the

surface, the work may seem dark and sinister, existing in sharp contrast of light and dark. however, light can only define itself through

darkness, and rarely does human spirit shine brighter than within a world of sorrow and despair. In these retablos all emotions and experiences, beyond good or bad, coexist to create the fabric of human existence.

Created on copper with a mixture of photographic images and paint, Antón’s retablos are small and function as both two-dimensional images and sculptural objects. The artistic form of retablos, also called ex-votos, has been part of Mexico’s tradition since the seventeenth century. The votive paintings on wood or metal panels were hung behind the altars of Catholic churches. Peaking in popularity in the mid-nineteenth century, retablos remain a tradition to this day. Unlike santos, which were painted portraits of saints, ex-votos were traditionally public expressions of gratitude in acknowledgement of specific saints, such as the Virgin of San Juan. The text on each retablo described a miracle credited to the saint, or a request for such a miracle.

Over the centuries, retablos have captured the magnitude of a people’s most trying experiences, including the recovery from serious illness or injuries, the survival of accidents, flights, or other life-threatening situations, or an unexpected resolution to financial or legal problems.

Retableros, the painter of retablos, were usually self-taught and rarely signed their work or considered the retablos to be works of art. As Antón explains, “there was no need to claim them as art as they served a higher purpose”. Frida Kahlo described retablos as the truest representation of the people’s art. Kahlo and her husband Diego Rivera collected them and many still hang in their home, which is now a museum.

Antón reinvents retablos as metaphorical documentation of the spiritual struggles of mankind. He uses the visual language of ex-votos to create existential tales of human existence that speak of spiritual searching, suffering, hope and despair; life and death. This overarching concept is expressed in the title, Ollin Mecatl, which refers to a Nauhautl expression for the measure of movements. The artist also translates this as velocity of change. He describes the concept as the “instances of time and tragedy and the reconciliation of hope . . . the core measurements of things lost and found, evidence of thought, and the resulting sum of solitude.” In Antón’s retablos all distractions of daily life have been removed to distill the essence of mankind’s passage through time.

Antón uses himself as the model in most images but the retablos are not self portraits per se. While he expresses deep seeded, highly personal emotions that may loosely include auto-biographical aspects, he also creates a message of universality.

His persoanl path leading to this work is one that side-stepped many perils and temptations. He avoided dangers that led some of his closest childhood friends to violent deaths, crime, and addiction. While not setting himself apart as being better or more fortunate than others, Antón humbly describes that he simply chose another path. He was not to go the route of this friends, and photography, which he discovered at age seventeen, was to change his life. Born into a family of laborers, he has done with art and passion what his parents had to do with physical work. He still tells of his father’s reluctant approval of his son’s artistic endeavors. Antón’s vision was born from the fruits of his family’s labor, and in return he has dedicated his life to teaching and passionate giving.

It is not easy for us to enter Antón’s world, nor is it free of pain or regret. By contrast, his world makes our comfortable existence seem void of life and passion. Having walked within Antón’s world and opened up to its intensity, we may find our view of our daily existence altered. As if returning from a trip abroad, it is not entirely certain that we will be able to readjust to our old ways of life that had previously seemed so entirely our own. Such is Antón’s gift to us.

Hannah Frieser is an extraordinary force in contemporary photography. Through her dedicated efforts as LIGHT WORK’s director, she has curated a diverse program of exhibitions and artist residencies which embraces the support and encouragement of emerging and under-recognized artists. An accomplished writer serving on the board of the Society for Photographic Education, she is also an extraordinary artist. Her delicate and thought provoking imagery address the issues of self identity and the complexities of multiculturalism. These intimate reflections may be viewed on her web site at www.hannahfrieser.com.

__________________________